Banana biology

Banana is one of the oldest cultivated plants. They are native to tropical South and Southeast Asia. That’s where the gene center is and, hence, the greatest genetic diversity of wild banana. Sampling that diversity is crucial for future improvement of the crop. A large collection of banana accessions is already maintained in the International Transit Centre.

The banana plant is the largest herbaceous flowering plant. So bananas don’t grow on trees! The banana pseudo stem grows 6 to 7.6 metres (20 to 24.9 ft) tall, from a corm. Each pseudo stem usually produces a single bunch of bananas.

After fruiting, the pseudo stem dies, but shoots – or suckers – develop from the base of the plant

and develop into a new pseudostems bearing fruit.

The female flowers (which develop into the fruit) appear in rows further up the stem (closer to the leaves) from the rows of male flowers. The ovary is inferior, meaning that the tiny petals and other flower parts appear at the tip of the ovary.

The banana fruits develop from the banana heart, in a large hanging bunch, made up of 3-20 hands, with up to 20 fruits (or fingers) per hand and weighs 30–50 kilograms.

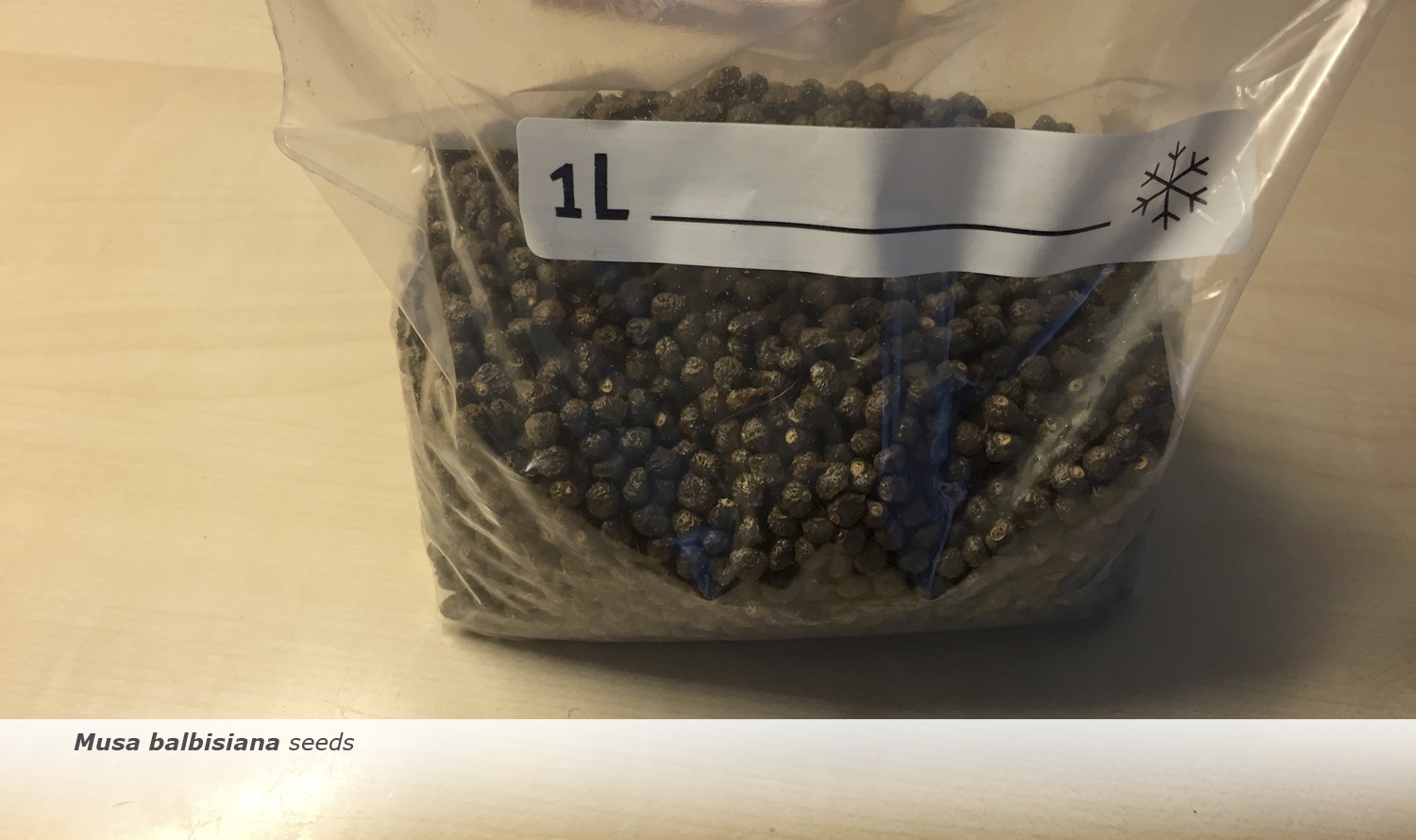

All widely cultivated bananas today descend from two wild banana species: Musa acuminata (AA) and Musa balbisiana (BB). While the original wild bananas contained pea-sized seeds (see picture above), edible varieties are

seedless as they result from parthenocarpy. (see picture in carousel above)

The fruit develops without fertilization of the ovule. This, evidently, affects propagation, which therefore typically involves farmers removing suckers and for industrial plantations millions of banana pants are produced through tissue culture.

However, nearly all commercial banana plants (i.e. the most popular ‘Cavendish’ banana we are eating today) are clones; genetically identical plants. Therefore, banana production is extremely vulnerable to disease outbreaks. The good thing is that plantations can be rehabilitated relatively easily after for instance typhoons that occur frequently in South-East Asia.

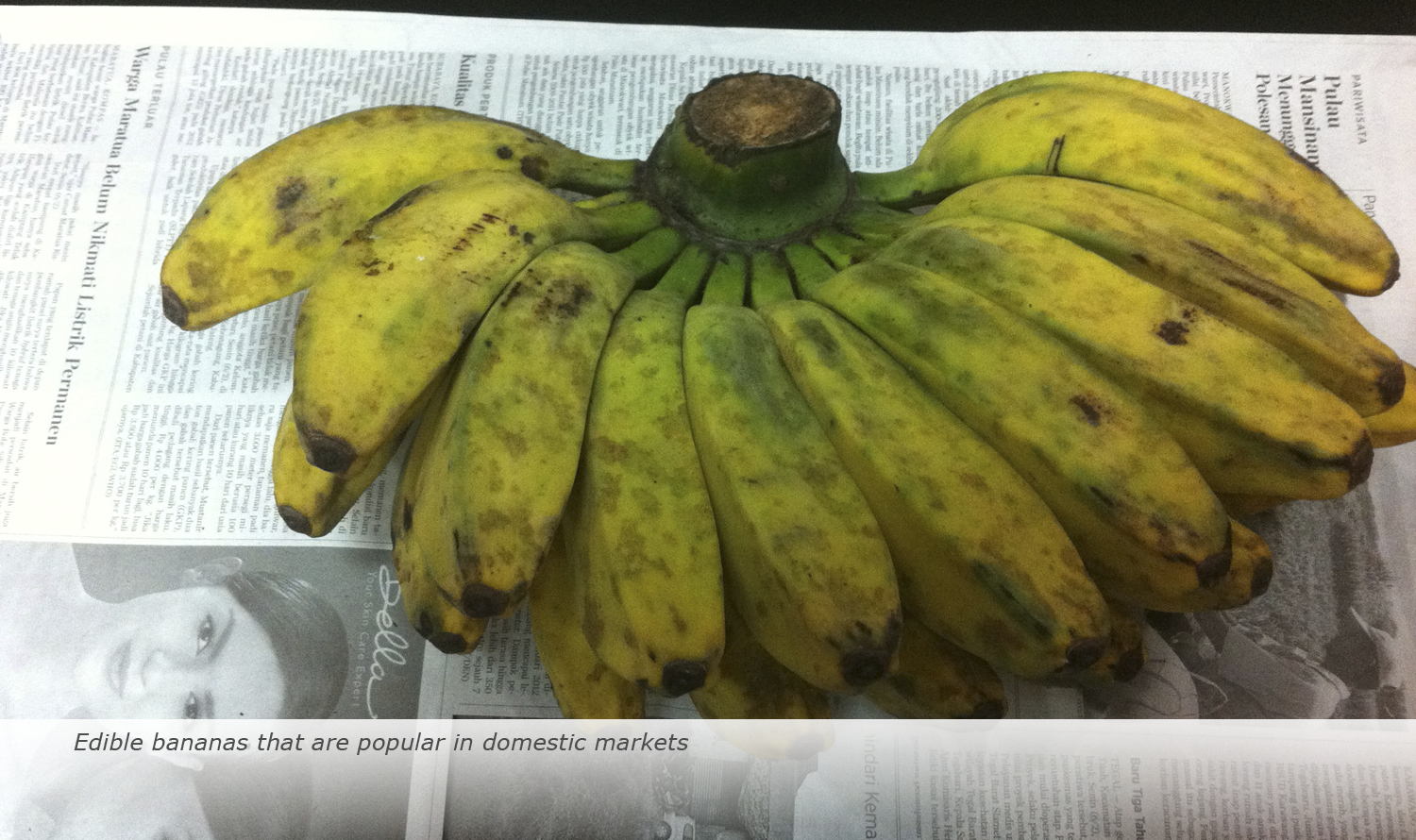

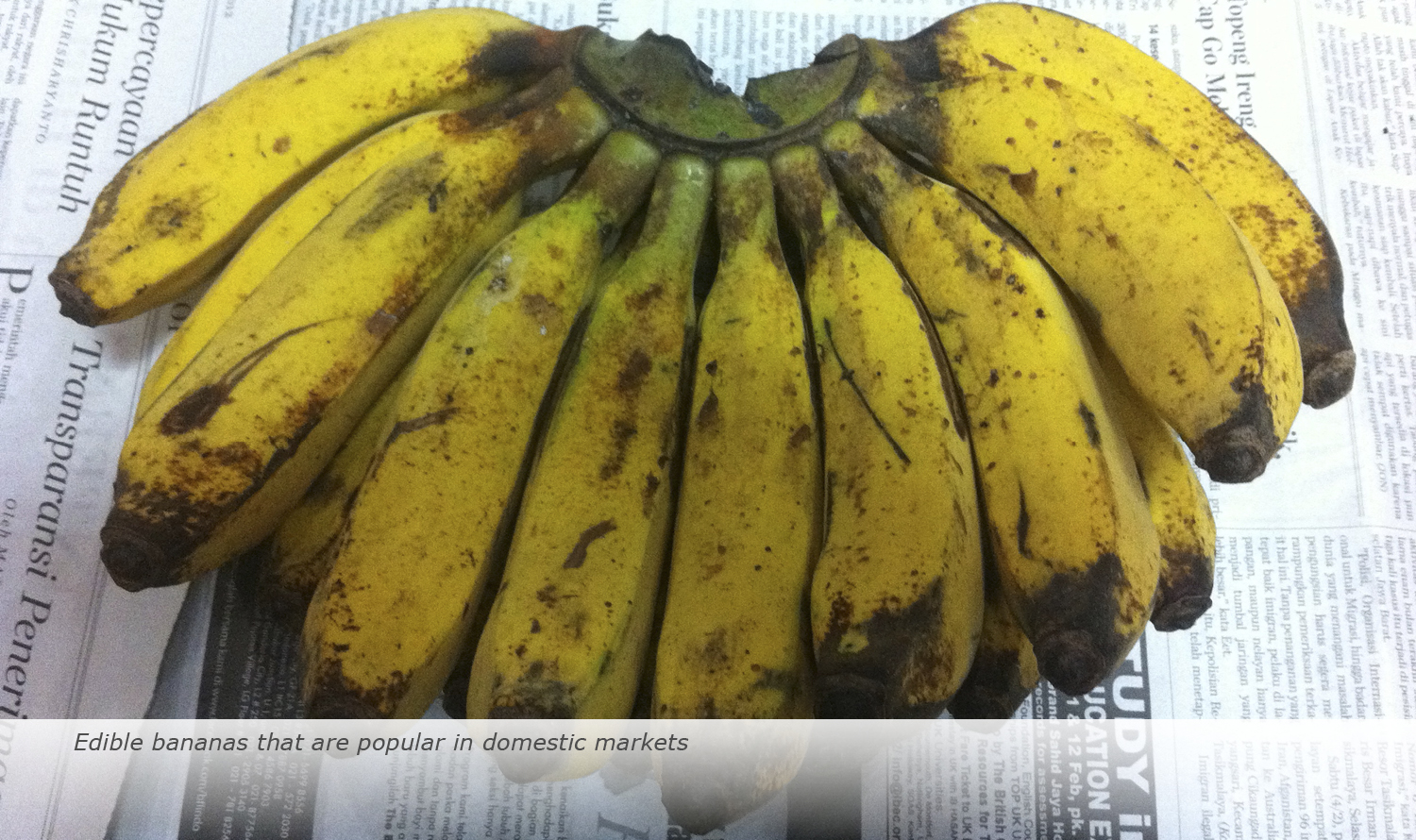

There are more edible banana varieties than ‘Cavendish’ (and remember whatever sticker you will find on your banana, the far majority is ‘Cavendish’).

The huge genetic diversity that is present in wild banana remains untapped as they neither can be consumed nor used in direct crossing programs with Cavendish aiming at improvement of banana.

Banana breeding is therefore a difficult and long-term task, which takes literally decades to release varieties that meet consumer demands. The sad fact is that ‘Cavendish’ succumbs to Fusarium wilt but there is not one banana variety that can replace it.

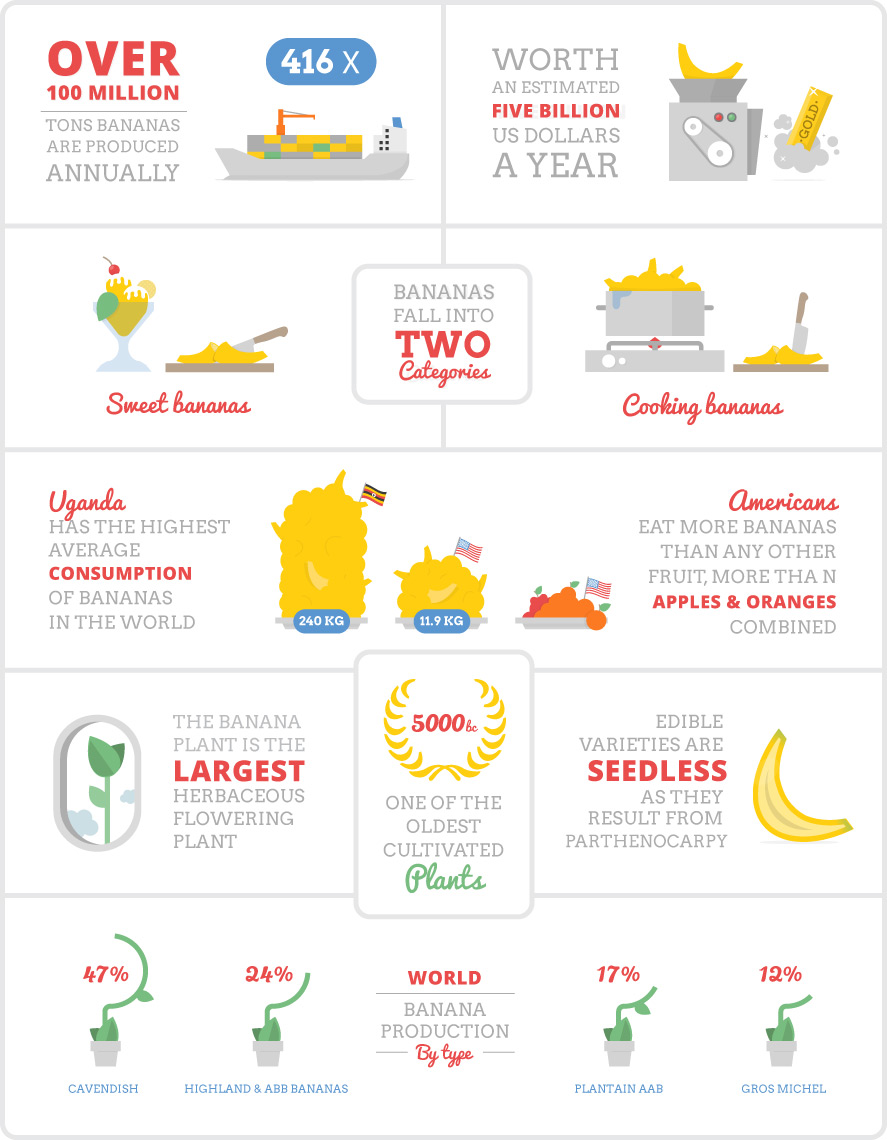

Banana facts